Vital Elements of the Product Design Process

Product design can look like magic. When I started doing it ten years ago, the small team I worked on made decisions intuitively. There was no system and it worked fine. But as the company grew, I found myself unblocking teams and diagnosing problems. When I saw patterns repeating themselves I decided to codify the questions I was asking. I hope that by sharing my techniques, people will learn to unblock themselves and diagnose their own product design problems.

The categories I introduce below aren’t arbitrary. They are extracted from years of solving real problems. They aren’t the only way to slice things, but they are the way I have used repeatedly with success. I can’t see any way to design without them, and when one is missing, things go wrong. That’s why I’m confident calling them vital.

You can broadly separate product design into two phases. First you come up with the concept of what you are doing, and then you implement it. The concept you come up with is like a map for the implementation. It tells you where you are, what you are working on, and what’s left to do. Many of us use iterative processes to implement. We learn through the process of iterating and change our original plan. I am not going to talk about the implementation phase. (I wrote about it here.) This article is about how you define the problem to begin with and how you get from there to a concept.

Three places to look for problems

Problems with product and feature design often trace back to the initial approach. Either the problem wasn’t well defined, the concept wasn’t well defined, or — in the case of beginners and newcomers to a platform — your bag of tricks wasn’t adequate to address the problem. Questioning each of these areas can open up new insight and unblock you.

I’m going to describe the problem you are addressing as the job a user is trying to do. We’ll look at the bag of tricks you bring to the problem in terms of patterns you’ve seen and applied before. After you know the job your product is supposed to do, and you have a collection of patterns from past experience, you can create a product concept. The concept unifies the relevant patterns you know into a composite design that does the job.

The Job

I need to relate the problem to a situation in order to understand it. The reason I am making a product is to give people capability they lack. That’s why they pay for it. The gap between the person’s current situation and the situation they want to be in defines value for them. They hire your product to do a job. The job is their definition of progress from here to there.

When the job isn’t well-defined, the team doesn’t know what to include and what to omit. They design based on logical speculations, not real situations.Instead of targeting a problem like a sniper, they cast a net and hope to catch the value somewhere within its expanse. Casting a net means building more functionality in more places, so the project grows in scope and complexity.

Sometimes people think they have defined the problem, but they really just defined a feature. Like “users want file versioning.” It’s important to understand that a feature is not a situation. You can dig into a situation to learn what is valuable and what is not according to the goal. Digging into a feature definition doesn’t do that. It has no origin and no goal. Analyzing a feature definition leads you to play out all the things a person might value from the feature instead of learning what they actually value.

Suppose a team is building a “file versions” feature. Two situations define the value differently and lead to different designs.

In one situation, a person catches an embarrassing mistake in a proposal and wants to know who to blame. In order to do this, they need to see information about intermediate versions. They value the product telling them who made what changes and when.

On the other hand, consider a situation where they want to send the latest version of the proposal to the client. They don’t care how it got to its current state. They just want to send the correct file. In this case intermediate versions have no value. The user just wants to know where the latest version is.

Deciding which situation you are designing for focuses the problem.Focusing the problem focuses the team. When the team knows where the value is, they stop speculating about all possible cases and they get down to business. It’s easier to make decisions about what’s in and what’s out. This leads to a clearer criteria for which patterns are appropriate, in turn leading to a clearer product concept.

Patterns

After you’ve identified the job, what enables you to do something about it? Your library of design elements and techniques separates you from a non-professional. Your patterns are the building blocks you combine into a product concept.

When we are beginners, we copy designs whole hog. It’s natural when you don’t understand how individual parts work in isolation. You’ll often see beginners template their designs after well known apps like Facebook or Basecamp.

As we mature, we see patterns at work in the designs we admire. Instead of copying Facebook whole hog, we realize a timeline is what we want for our design. Patterns like collection view and detail view, nav bar, and multi-step process enter our vocabulary. These large scale patterns structure our designs.

There are patterns on the small scale too. Within a stream of comments, you design the display of an individual comment. There might be an avatar on the left to anchor the block, or a bold name on top. The time stamp might sit below the header or float to the right in its own space.

Some people think patterns are formal things written in a book or collection, but they aren’t like that. They are natural and spontaneous just like spoken language. We learn a language by hearing it and speaking it. Words, phrases, and constructions come to mind as if by magic. We don’t hold a dictionary in our hand as we talk to people.

In the same way, we learn patterns by exposing ourselves to designs and designing ourselves. We put elements together and learn what works and what doesn’t. Then, just like our habitual words come to mind more easily than others, the patterns we used with success will appear again and again in the face of future problems.

One thing to watch for with patterns is the beginner mindset I mentioned.We’ll sometimes copy whole designs without knowing how they work. This also happens when we work on new platforms. Until we speak the native language of, say iOS, we will find it easier to follow what other apps do and whatever is easiest in the APIs. This a natural learning process, but we should be conscious about it. Otherwise our product concepts will be limited by our small vocabulary and they won’t target the job as well as they could.

The Product Concept

When we apply our patterns to the job we create a product concept. It is a whole idea knit out of patterns that solves a problem. It often takes the form of some key sketches or mockups that define the project.

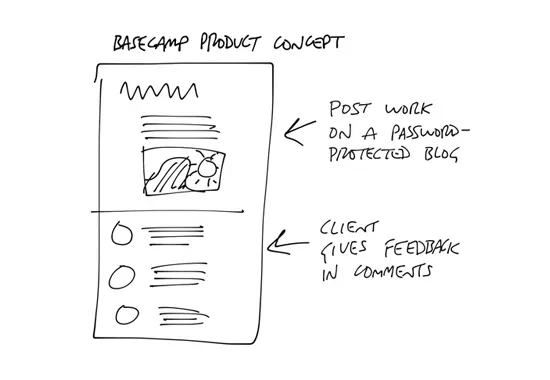

Here’s an example. Basecamp grew out of a very focused concept.

37signals was a web design company in 2003. One person talked to the client and another did the design. When we showed work to the client, it was a game of telephone back and forth. Doing the design was simple but showing it to the client, passing the feedback around, and submitting new work for review was a mess.

We wanted something to make it easier for us to show work to the client and get feedback. That was the job.

Blogs were a new phenomena in 2003. The patterns like posts, comments, and permalinks were high in our minds. We had also seen things like password protected web pages and interfaces for user management.

We put these patterns together into a product concept: a private project blog where you could post work to clients and they could comment on it. That’s the heart of Basecamp.

Sometimes teams start building without an explicit product concept. It’s easy to do that when you think you understand the problem and you’re confident in your skills. The problem is that when the concept isn’t explicit, the project becomes a drunken walk. It becomes opaque and hard to estimate because the goal isn’t clear.

A product concept gives you a map of the territory you are trying to cover during implementation. Looking at that map shows you which areas you covered and which ones you haven’t yet. It helps you answer “are we there yet?” with more precision.

Be wary when technical people on a project start implementing without an explicit interface or end-point in mind. Good product development is a sequence of bets. You bet on a concept, implement it, and test it in context.Did it do the job? What worked and what didn’t?

The goal of the design process is to reach fitness between problem and solution. The job defines the problem and your concept defines the solution.The moment of truth happens when you fit the two together. That’s when you test your bet.

If you aren’t explicit about how you defined the problem versus how you build the solution, you will get lost in debate when things aren’t right. One person will be talking about the problem while another is questioning the solution, and yet another person is pointing out details of the execution.Focus on one aspect at a time to make the debate productive.

General and recursive

If you take time to consider the three elements, you’ll discover they apply at many scales of a project. A product has an overall job and concept. Each feature has a job and concept. The same applies to individual methods in the code. And there are patterns at all levels, from large scale structure to individual design elements to code choices.

The generality of these elements makes them powerful. This article itself is designed for a job (debug problems in a product design), uses patterns of construction (illustrations, headers and paragraphs), and follows an overall concept (the three elements as a system and their one-by-one explanation).

When you should not use this

Since this article is itself a product, there are situations where it is valuable and those where it isn’t. It applies when you are struggling to reach a particular goal. Problem definition and concept definition help us to the extent that we are trying to get somewhere in particular.

This works against you when your work isn’t goal-directed. R&D projects and exploratory design don’t benefit from narrow problem definition. Platform and infrastructure projects are different in kind from product projects because the platform is meant to enable products on top of it, which are themselves targeted at specific situations.

The more you are trying to provide specific capability for a specific situation, the more these vitals elements — the job, your patterns and your product concept — take you there.