Shaping on the demand side

One day, back in April, I was shaping some work for Basecamp 4 (the next version of Basecamp that we're planning to build next year).

At 4:00 p.m. I got an alert from Basecamp's Automated Check-in, asking: "What have you worked on?" Normally I write a few bullet-points to summarize what I did.

I felt hesitant and anxious about answering. I was doing research and trying to figure out what problem to solve. I could write "more research and exploration" in my check-in answer, but that felt so ... undirected.

I know (and people reading my check-ins know) what typical product research looks like. It's like gas particles filling the air. The more time you allow for it, the further it spreads out, and the further you get from a decisive conclusion.

If I say I'm sketching, mocking, prototyping ... those sound constructive. I'm getting somewhere. I'm making something. It's coming together.

"Researching" can sound like I'm wandering, circling, or just collecting more and more data, when in fact I'm digging in a specific place and building up a specific understanding to guide my next steps. Saying "more research" just didn't communicate the forward progress I felt I was making.

On a parallel train of thought, Shape Up was getting a lot of attention, and I was aware that it didn't define the early stages of shaping very well. I wrote about turning a raw idea into an actionable concept, but I didn't write about how we improve our understanding of the problem or narrow down where the opportunity lies.

So I wrote this Tweet:

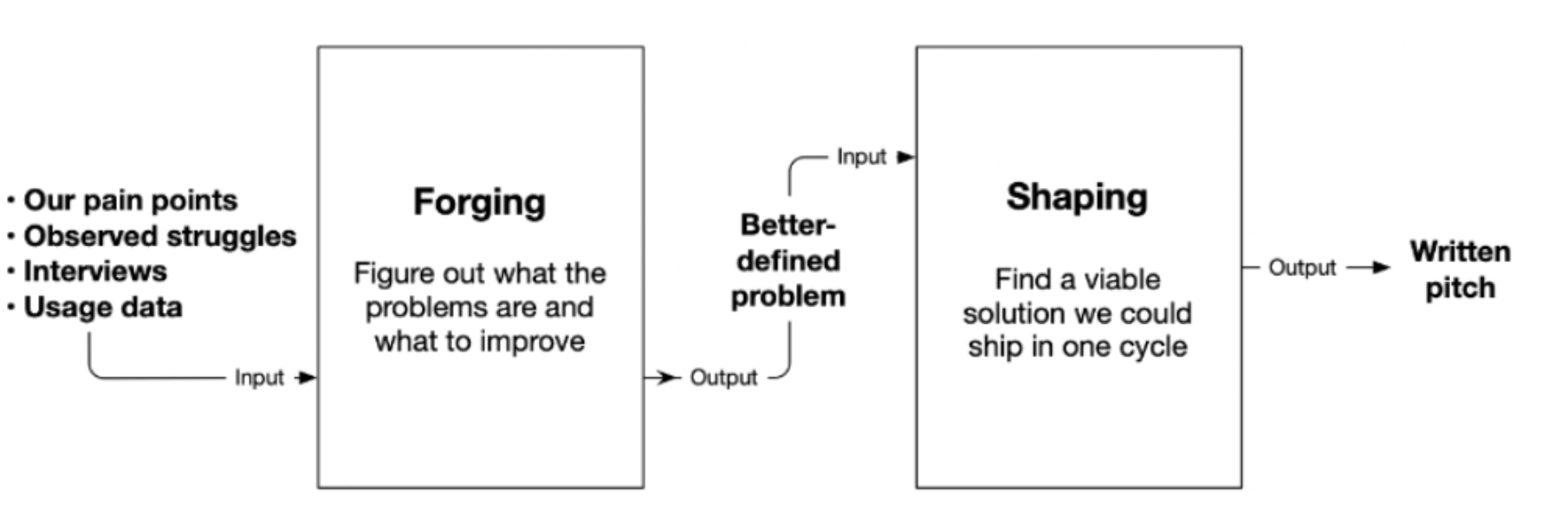

I tried to define "forging" as an input to shaping. It's different work than research. It's work that takes research as an input. The output is a better understanding of the problem that gives you more clarity about what to do and not do.

The name wasn't right. I was sure this is a legitimate step to call out. There is a transformation there that corresponds to a specific type of work. But calling it "forging" felt ... forced. Many folks suggested other names on Twitter, but they didn't stick either.

Fast forward six months later to this week. I was reviewing some old posts to prepare a talk about Basecamp 4. In the time since I posted the "forging" image, I've been thinking more about supply-side versus demand-side framing. (Bob's book Demand-Side Sales 101 is a good example of this.)

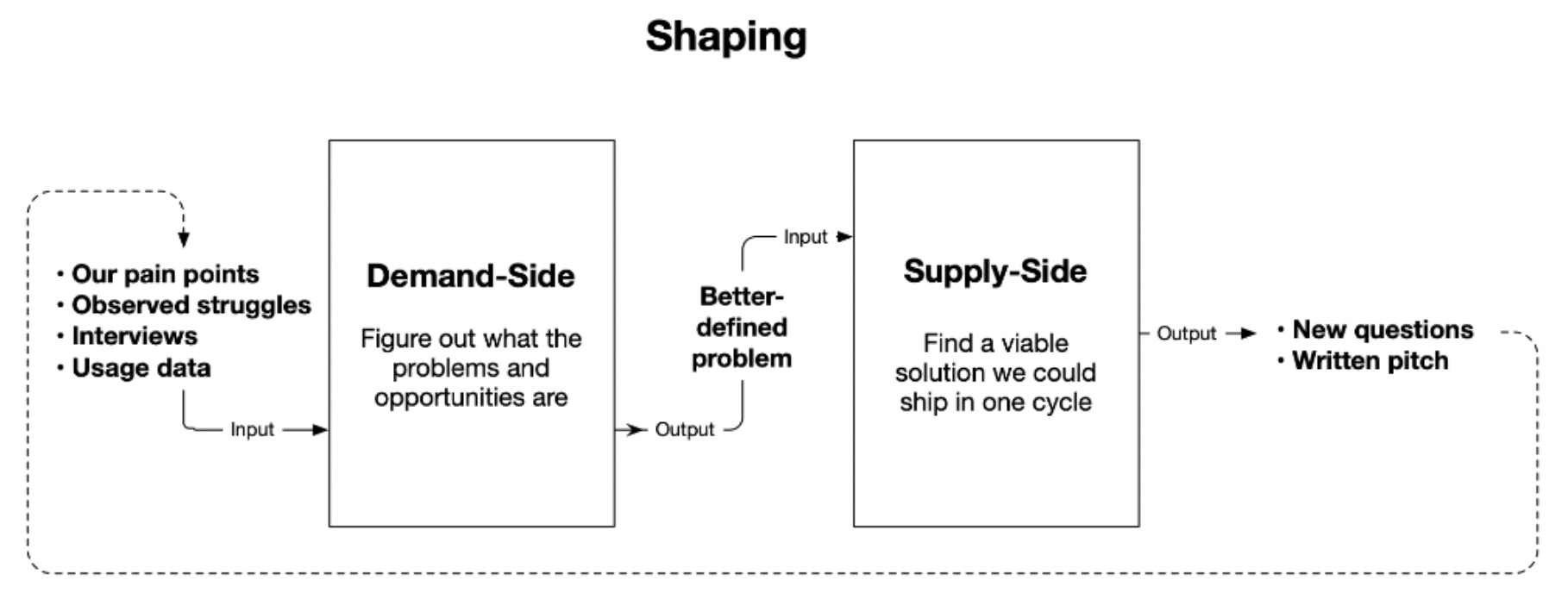

Then it clicked. What I called "forging" is actually shaping on the demand side. "Shaping" captures the fact that it's integrative, constructive, and leads to an answer. "Demand side" means it's about what people do, the circumstances they're in, and the outcome they seek. Taken together, shaping the demand side means integrating what we've learned about real behavior to synthesize an understanding of the problem that constrains the solution.

Contrast that with shaping on the supply side, where we construct the key patterns and relationships that can generate a solution.

That led to a better picture with less arbitrary, more coherent language:

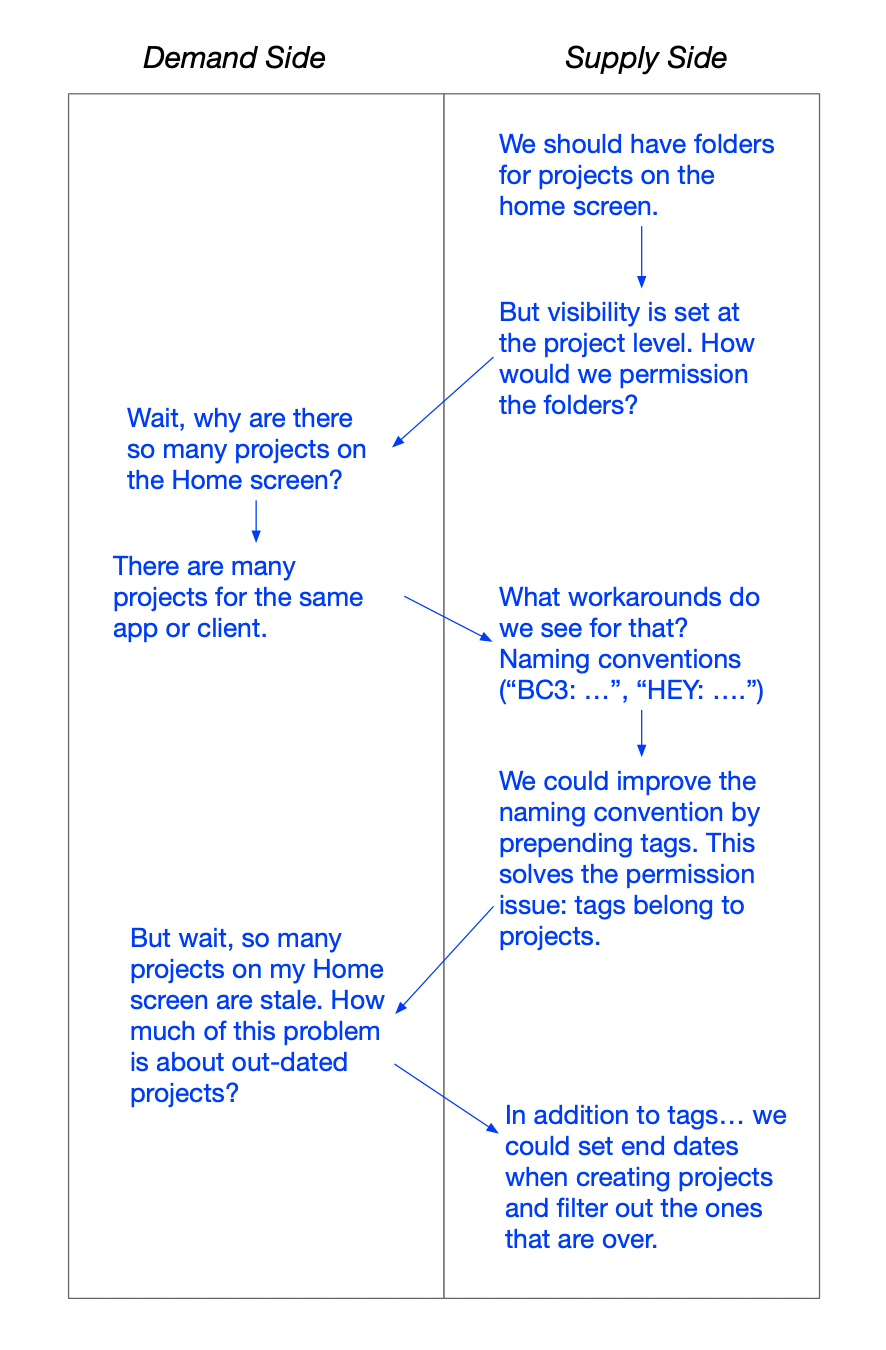

In case that looks theoretical, here's a concrete example.

Shaping can start on either side. Sometimes you have a problem and no solution. "It's too hard to find things on the Basecamp home screen. It looks like a mess."

Other times you start with a solution, but you haven't yet worked backwards to the problem. "We should offer Folders on the Home screen."

Here's a recap showing how I moved back and forth between the supply-side and demand-side while shaping an idea for Basecamp 4. It started with an idea to offer folders. But then this led to some questioning, which led to some research, which led to a different conclusion about what to pursue on the supply side.

Some of these steps involved diving into research on the demand-side or prototyping on the supply-side.

For example, when I suspected the home screen was cluttered from out-of-date projects, I ran data to see what proportion of projects on our own company Basecamp account were shown on the home screen but hadn't been touched in months. I discovered it was a huge issue for us.

That research wasn't random curiosity. The back and forth between the supply side and demand side defined a context that made it clear at each step what the question was, why I was asking it, and how the answer affected the work-in-progress solution.