Products Are Functions

Products are easier to reason about when you think of them as functions. They transform an input situation into an output situation.

This lets you describe what the product does as a transformation of the user's circumstance instead of a bundle of features.

How a product is like a function

Consider Basecamp. What is it? A central shared message board? A to-do list manager? Those things describe the solution — its capabilities. But what does Basecamp do for its customers?

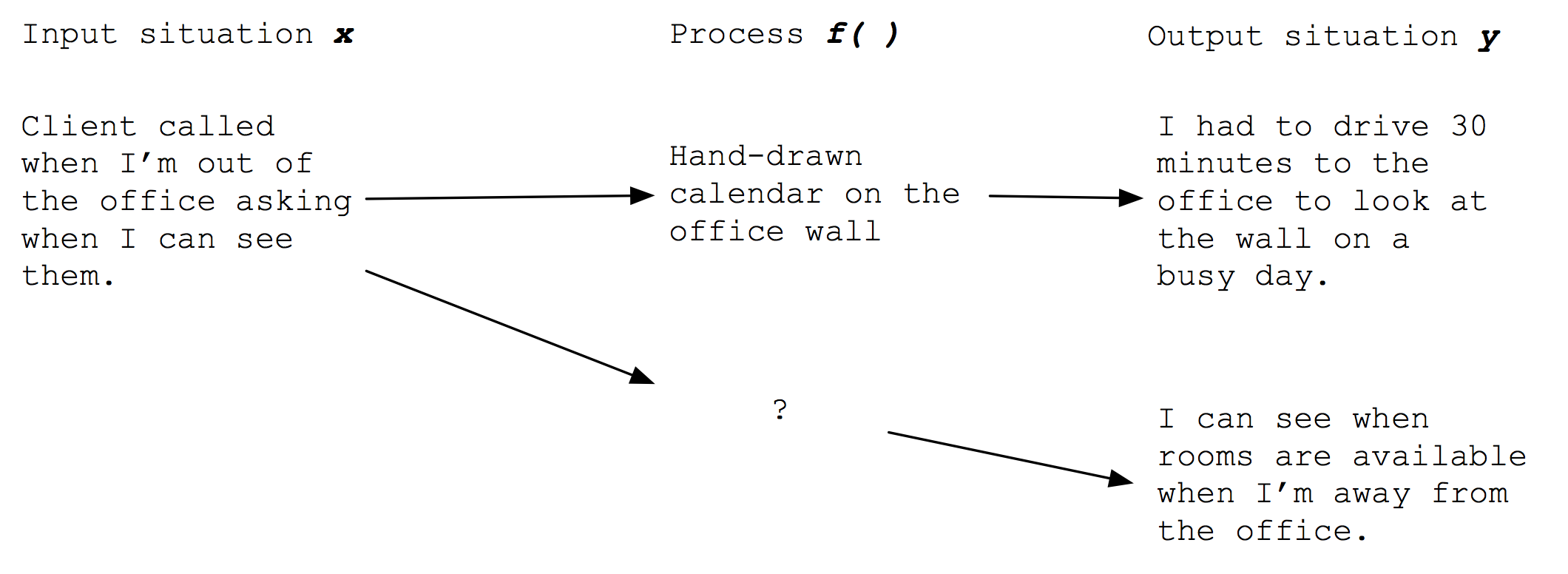

Recall the definition of a function: some input gets transformed into an output. You have a function f(). You run x through it and you get f(x) = y.

The user starts in some circumstance x. Whatever product or solution they apply is a function f(). Applying the product to that circumstance f(x) produces a result: y.

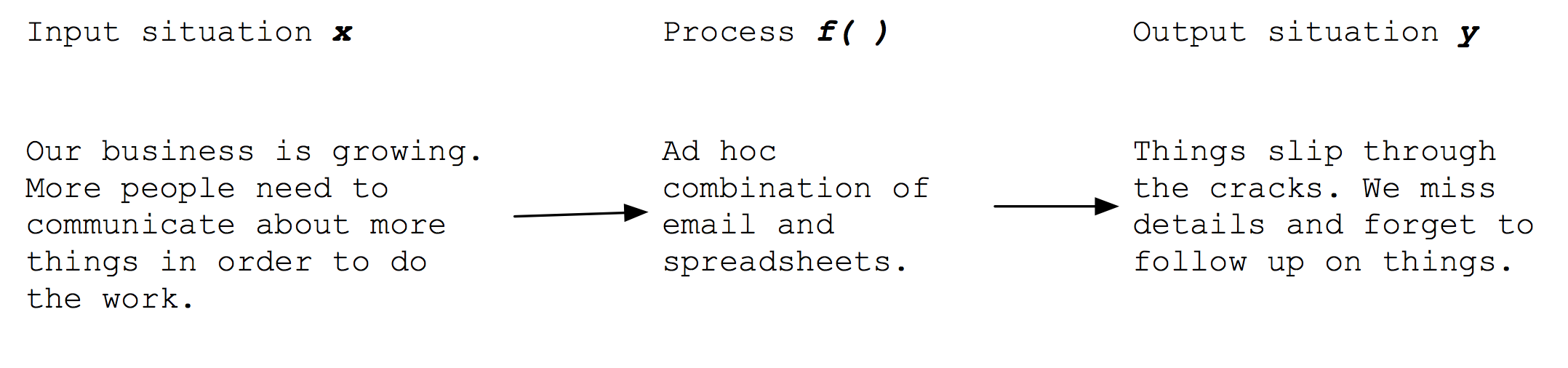

Consider the situation before someone buys Basecamp:

Email and spreadsheets aren't inherently bad. But when the workload gets too big, or too many people are involved, they create a bad outcome.

Now, keep x the same and plug in Basecamp as f() for a new y.

Basecamp takes the same situation and creates a different output. This is a much more precise definition of what Basecamp does than "team collaboration" or "project management."

* It's not the only case, by the way. Products can perform more than one function.

What do you get from thinking this way?

A definition of 'requirement'

The product designer's task is to create a new f(). The designer doesn't get to define x: that's empirical. And they don't get to dictate y either. A given y is only a worthwhile target if it's worth paying for in the eyes of the user — also empirical. That means x and y are requirements for f(). They are fixed, f() is variable.

Most designers set requirements for f() by describing what f() should be, which is a circularity. To be useful, requirements should be defined independent of f() as tests for fitness.

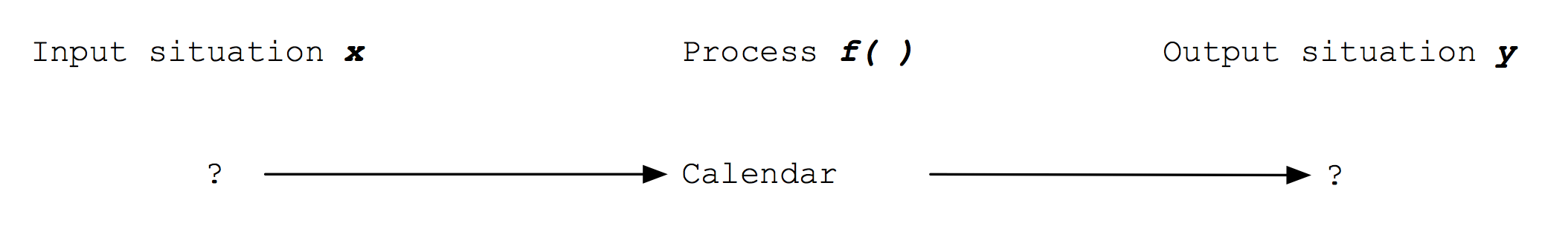

Here's an example. A customer writes in and says "I want a calendar in Basecamp." They've defined a function:

How do we know what to include in this calendar feature? Does it need to allow you to drag events between days or reposition meetings minute by minute on a day view? Or send out invites to events? There are no requirements here.

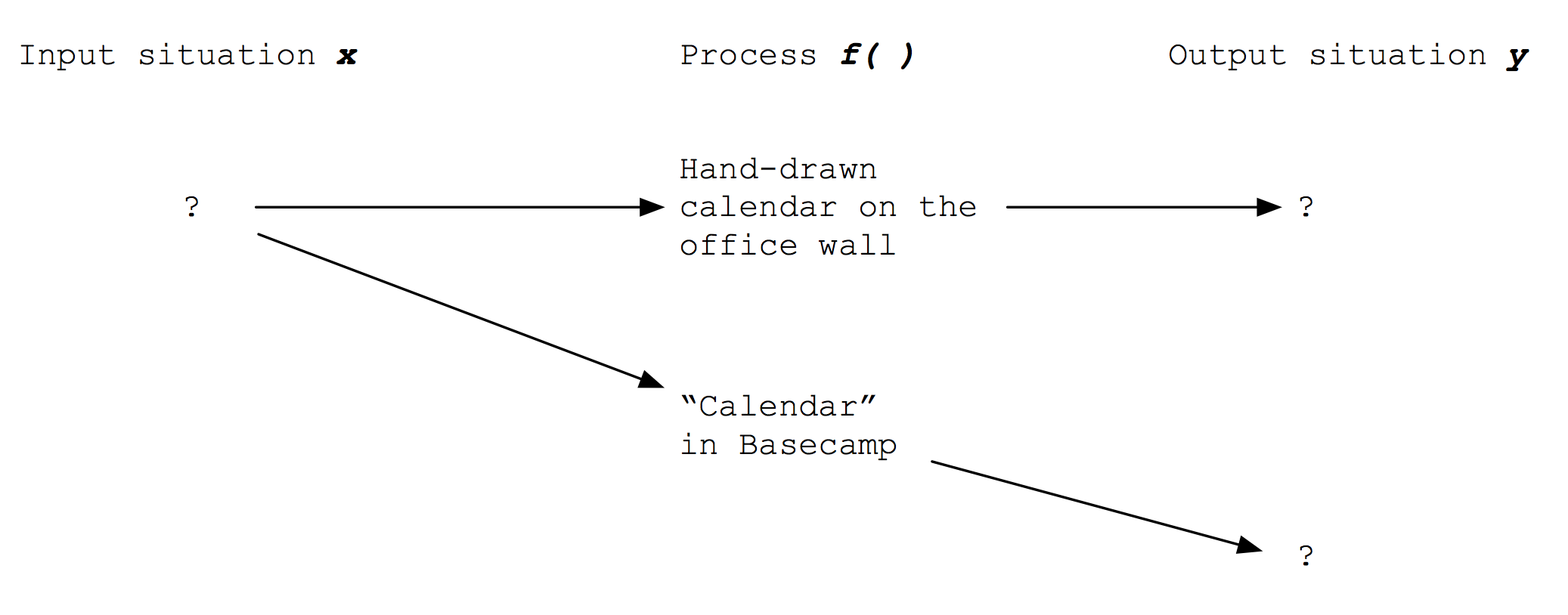

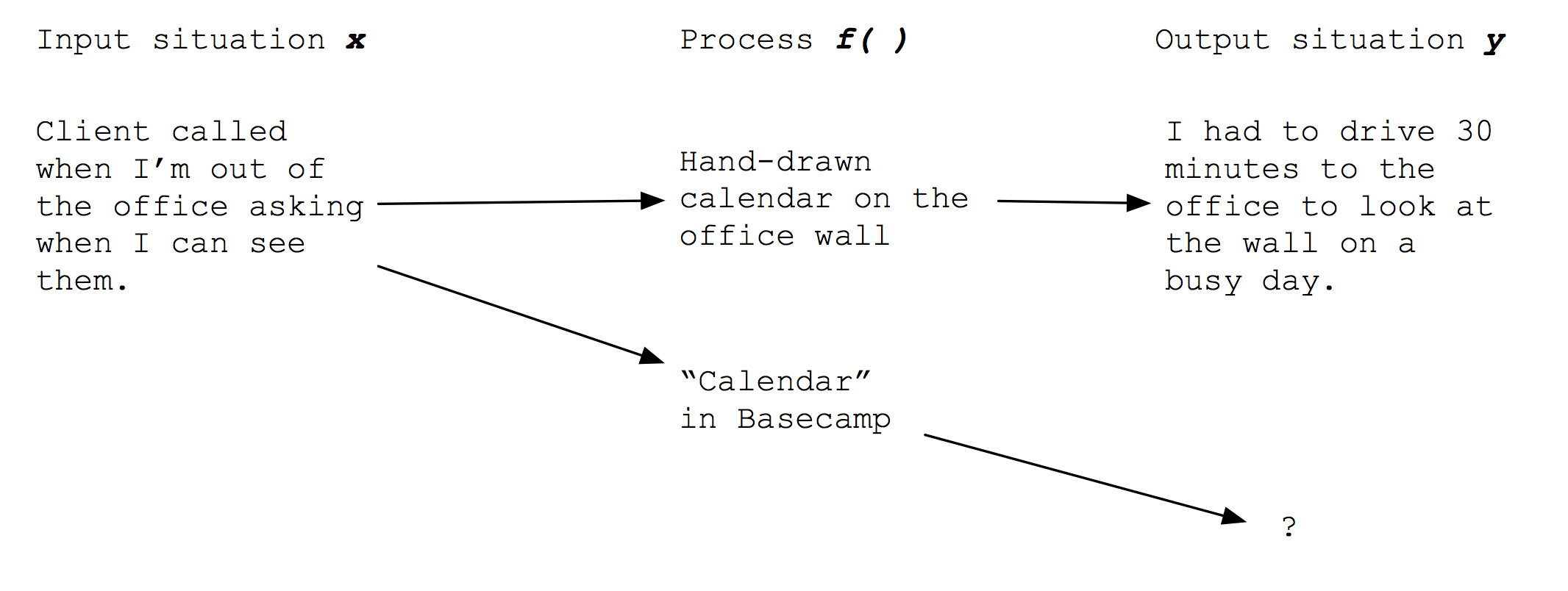

Time to do some detective work. We get on the phone with the customer. What are they using to deal with this today? She says they have a calendar painted on the wall in their office.

What's wrong with this? What was the situation and outcome that made the hand-drawn calendar a bad fit? More detective work:

Her team used the wall calendar to reserve rooms to meet with clients. This function broke down when she got a call from a client when she was away from the office.

Solve for f()

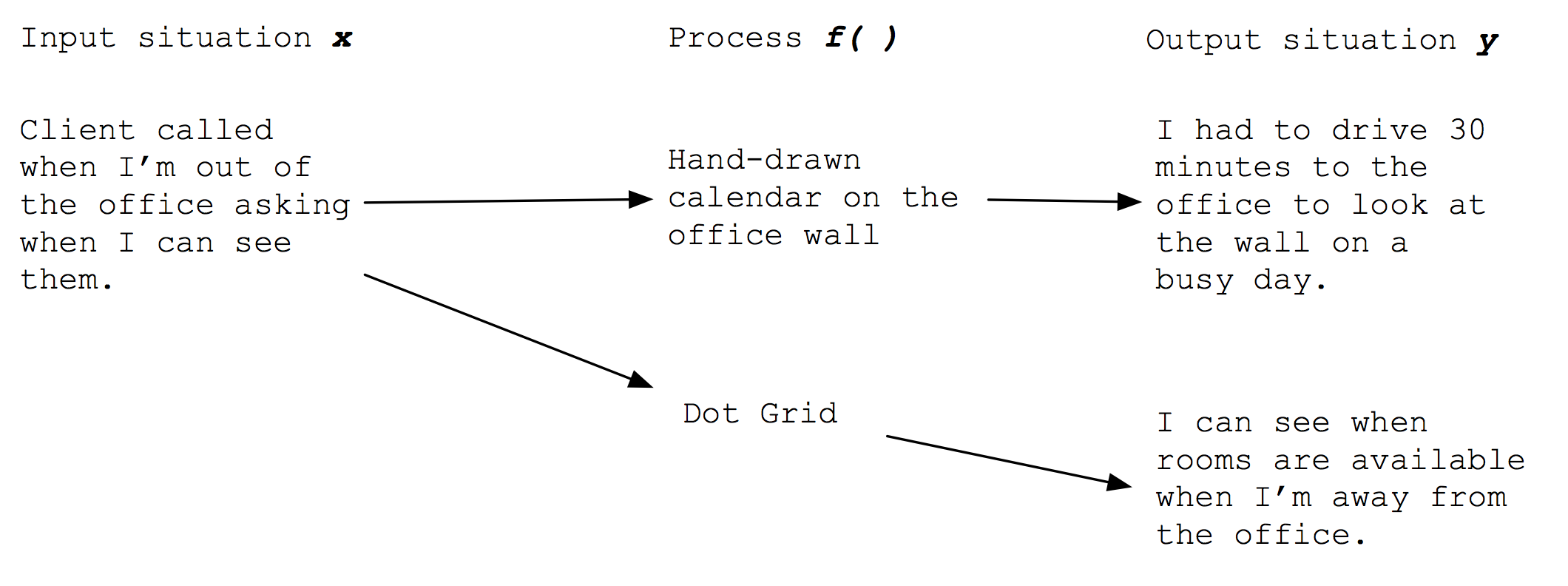

It's time to flip this inside out. Now we know what y should be: "See room availability when I'm away from the office."

We could go ahead and build a calendar for that. But calendars are expensive to build with no clear end to the scope. Could we come up with a different f() now that we know x and y?

Now we can reconsider the solution — the function to design. What are the requirements telling us the function needs to do? The problem is seeing available spaces. It's a resource scheduling problem.

This opened up our minds to consider things like booking systems and appointment scheduling interfaces. We looked at a variety of low-end calendar and scheduling app with the question: is this good enough to simply find an available time?

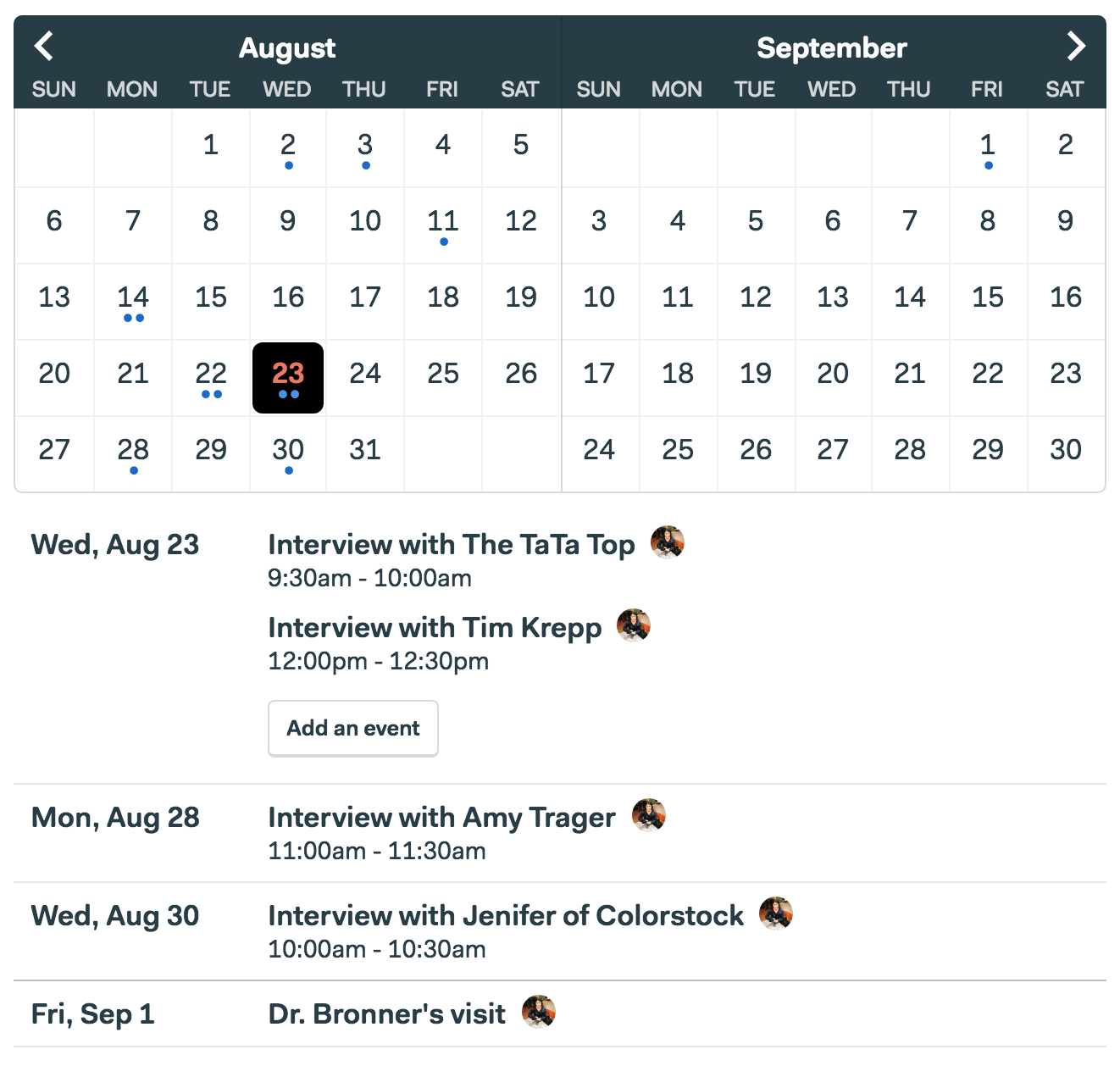

In the end we designed an extremely stripped down interface we called the Dot Grid. All it does is display dots on a monthly grid to indicate which days have something scheduled. Clicking a day cell reveals the events scheduled in a list below.

The "Dot Grid" solution was 10x faster to implement than a full-featured calendar.

There are no other views and barely any standard calendar behaviors. The project was 10x cheaper and faster to build than any other 'calendar' concept we could think of prior to redefining the requirements.

A way to define better/worse

This question often plagues design teams: is it actually better? How do we judge?

When you frame the product as a function, you can answer this question by comparing the outputs.

Very often designers are comparing "up" to an ideal solution (which is never reached), rather than "down" to the status quo. This functional view of the product makes that comparison to baseline explicit.

Baked in time and causality

Lastly, the functional view bakes in causality. Customers make decisions in situations to achieve outcomes, rather than purely based on likes and dislikes. This framework forces you to think about what happens before and after they use the product.

Designers often debate what is "good" in the absolute. As a result, fashion and personal preferences influence the solution more than casuality and context. Finding empirical values for x and y enables you to consider what needs to happen step by step to produce the right specific outcome, thus guiding you to a unique solution tailored to the problem at hand.